Student field study: how coffee beans can lift farmers out of poverty

.

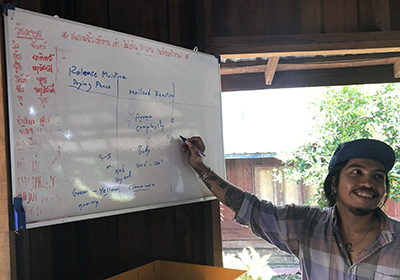

KTH students David Sigge and Filip Borgström spent two months in Thailand as part of their degree project in industrial economics. They looked at if and how farmers could increase their income in a sustainable manner.

“Thailand is a great country for field studies,” says Borgström.

With a grant from Minor Field Studies, Sigge and Borgström travelled out there in February and were welcomed by Wimolsiri Pridasawas, Professor at KMUTT and a former PhD student at KTH.

As well as studying sustainable farming methods, they wanted to contribute to the university’s work against deforestation, and to boost living standards in Ratchaburi province, where 30% of the population lives below the poverty line. One hypothesis was that greater knowledge about Robusta beans, which thrive under the forest canopy, could be part of the solution.

Working from their simple rented home and base on the outskirts of Bangkok, the students visited several farms that grow coffee crops, amongst other things. Borgström tells us that the global market associates Robusta with poor quality – the beans are often harvested before they’re ripe – which means that much of the harvest ends up as instant coffee.

“In Thailand, a few people are working to disprove the stereotypes. If you use the right technique, it is actually possible to make quality Robusta coffee. It’s considered healthier and contains more antioxidants and caffeine than Arabica. I’ve been drinking it a while now and I find it has a nicer finish, not as bitter or burnt as I’m used to.”

Coffee crops are, however, just a small proportion of what the farmers produce. The average Thai farmer has no knowledge of the process and sells the beans for a mere SEK 15–16 (about €1.3–1.4) per kilo.

“But the farms we visited knew about processing and refinement, and we saw examples of whole communities essentially lifting themselves out of poverty,” say Sigge and Borgström, adding:

“On those farms, they know when the beans should be harvested, how the fruit should be peeled and how the beans should be roasted to bring out the best flavour.”

Creates an eco system

In Thailand, trees are felled to clear land for crops such as maize and sugar cane, increasing carbon dioxide emissions and reducing biodiversity. But more sustainable methods that can replace industrial farming are on the increase.

“Chemicals and fertilisers drain the soil of nutrition and eventually leave only sand. The farmers we met take a different approach. They started by growing banana trees, whose roots attract biological material. A year or so later they had revitalised the soil and created an ecosystem. The farming there is more resilient to pests, drought and flooding,” says Borgström.

Sigge emphasises that coffee growing in and of itself is not a panacea for the problem.

Becomes instant coffee

“But if it takes place in combination with other crops like rice, cacao, bamboo and durian, the diverse harvest generates more profitability. Arabica is under threat from climate change, so we will be seeing more Robusta. It’s more resilient as it’s grown at lower altitudes, so it’s not as sensitive.”

How would you sum up your eight weeks, meeting other students and even taking diving lessons in Koh Tao for four days?

“We’ve learnt an incredible amount and increased our understanding, not only in terms of academic study but also how people live in rural areas. Everyone we met was moved by the fact that we were there. Thailand is a great country for field studies, with big cities, beaches and a lot of countryside. We had no kitchen, and even though we ate out every day my whole trip cost just 40,000 kronor (€3,500) including flights and rent,” says Borgström.

“We would never have seen most of the places we visited as tourists. We had a basic idea of things before we went, but we realised it’s far more complex. It’s interesting for example that food is so cheap but sweets are expensive,” says David Sigge.

Lars Öhman

Photos: Private

Read David Sigge's and Filip Borgström's (pdf 675 kB) travelogue