Autonomous vehicles en route to the city

The automobile with a mind of its own is a recurring fantasy in TV and film dating back to the 1960s. But it’s nearly time for KITT, Christine and Herbie the Love Bug to pull over and let some real-life autonomous vehicles pass.

Self-driving vehicles are already used in mines, ports and freight facilities. But if they were deployed on a wider scale, driverless cars could potentially improve road safety, traffic flow and energy consumption. At the Integrated Transport Research Lab (ITRL) at KTH, Director Jonas Mårtensson is leading the work to get these autonomous vehicles (AVs) out on the street.

“The big challenge for self-driving vehicles is coping with complex situations,” Mårtensson says.

Think missing pavement markings, incorrectly parked cars, electric scooters and food delivery mopeds. Think snow and bad weather. These “last 5 percent percent of traffic situations” are what a newly-launched research project, FOKA, is working to solve, together with Nobina Technology, Telia, Stockholm’s regional government and others.

Mårtensson sees a way to bridge these gaps in a vehicle's judgement by connecting them to control rooms staffed by human operators— or virtual control towers, as the researchers call them.

In the FOKA project, self-driving vehicles are connected to such control centers, and the operators can help when needed. One possibility is for each operator to handle 10 autonomous vehicles, though there are limits to how quickly control operators can intervene in dangerous situations.

“The vehicle must always be able to stop safely by itself,” he says. “Then an operator in the control tower can log in and give instructions, or remotely control the vehicle.”

Check for various obstacles

FOKA builds on the research project Autopiloten, in the Stockholm suburb of Barkaby, where a self-driving bus provided feeder service to local commuters for a few years. Now the researchers are moving forward with a number of new issues.

“The project is about understanding what is required to replace the driver,” Mårtensson says. “You need a high degree of automation with sensors and data, and you need to cope with different weather and complex situations. It is also important to be aware of various obstacles: technology, legislation, data sharing, business models for upscaling and how travelers accept and experience the technology.”

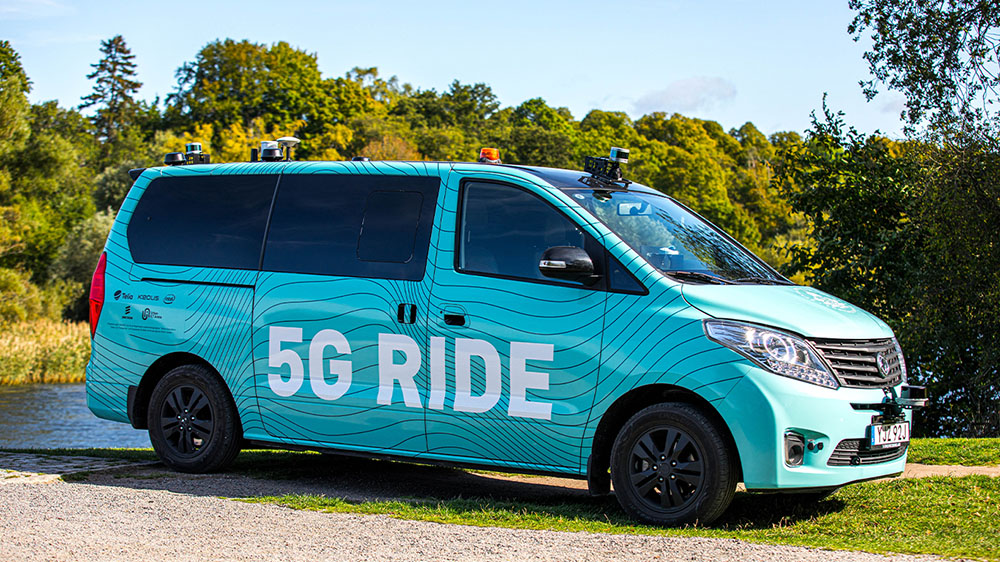

Another research project in which KTH participates is Future 5G Ride, in partnership with Keolis, Ericsson and Scania, among others. The project is to develop and test technical conditions for introducing driverless vehicles in mass transit and freight transport on public roads in a safe and secure manner.

Dynamic driving scenarios

But before we can retire the Knight Rider, Mårtensson says a number of things need to be in place: mobile networks with reliable 5G service, vehicles that share sensor data about the roadway environment, and connections to control towers for monitoring and assistance.

“Driverless vehicles with passengers today only drive short, static routes in individual test projects,” he says. “They don’t yet have all the technical prerequisites for reading the surroundings in a safe way. With today's complicated traffic rules and complex situations in urban environments, driverless vehicles fail to make decisions about contradictory situations. Vehicles may not be in control in all conditions due to very dynamic driving scenarios.”

Pros and cons

But self-driving is not an end in and of itself, Mårtensson says. If traffic can be controlled, it can also be evened out so that there are fewer traffic jams. Also, an autonomous vehicle can run more fuel-efficiently than one driven by a human.

"If you eliminate the cost of a driver, the vehicle can go slower, for example at night, which both improves passability during the day and reduces energy consumption. It can also lead to vehicles being built differently."

Driverless cars offer many possibilities, but recoil effects can also occur. If it becomes cheaper to transport by road in self-driving vehicles, demand will increase and there will be more transport and more traffic, perhaps even transferring loads from trains to the roads.

"There is a risk that driverless vehicles go around empty when they have to pick up the next person, and that in this way there will be larger traffic volumes. So we need to study this in a bigger perspective as well, and not just look at technological developments."

Peter Ardell/David Callahan