Energy technology that cuts emissions

The principle and technology are similar to those found in refrigerators, tumble dryers and ice rinks. However, high temperature heat pumps (HTHP) are based on a more advanced and powerful technology that can save energy and radically reduce emissions from both buildings and industry.

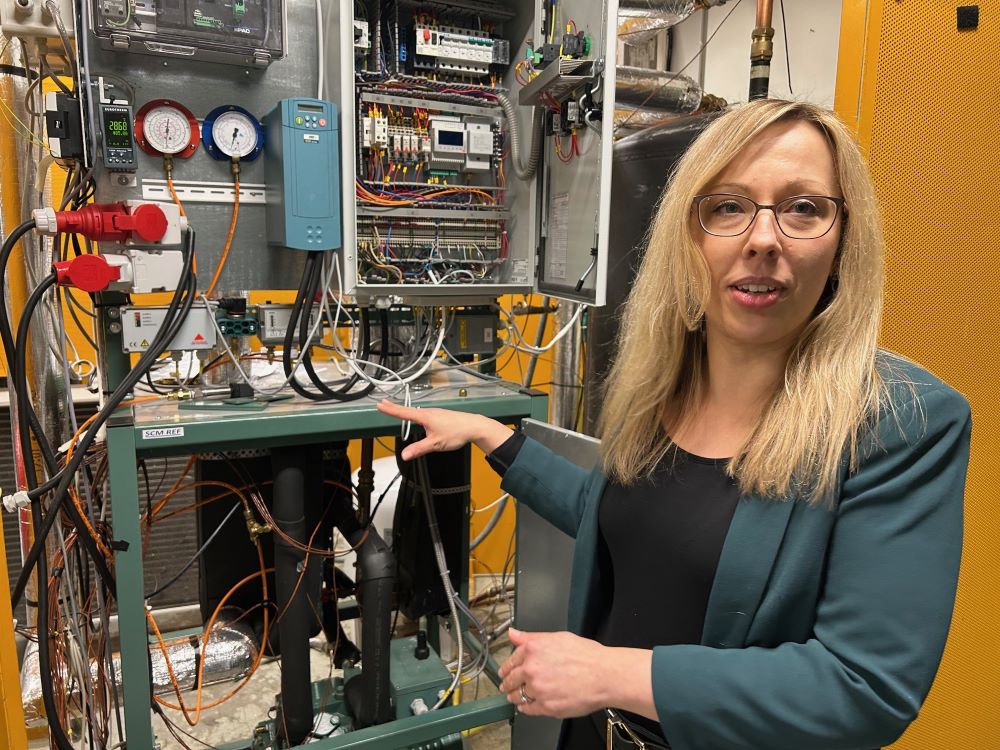

"The technology, which is relatively new, is constantly improving and has enormous potential in terms of energy efficiency, but there are still challenges that require further research," says Monika Ignatowicz, PhD student at KTH's Department of Energy Technology.

The development of high-temperature heat pump technology has really taken off in the last 20 years, as the technology has become more and more in demand due to increasing demands for energy efficiency and reduced carbon dioxide emissions in order to protect resources and the climate.

Long tradition at KTH

Conventional heat pumps have been used since the early 1900s, and KTH has a long tradition of research in the field, which has laid the foundation for the development of today's high-temperature heat pumps, in which Sweden and KTH have a strong international position.

The energy demand for heating and cooling in industry and housing is enormous. It accounts for more than 50 per cent of the EU's total energy consumption and is expected to grow. In Sweden, the picture is somewhat different, as we use more energy from renewable sources. In the work on decarbonisation, i.e. phasing out fossil fuels and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, HTHP can make a big difference.

Both the Swedish climate targets and the EU's Fit for 55 climate targets call for a significant reduction in emissions by 2045 and 2030 respectively.

"Existing HTHP technology can meet about 10 per cent of the industry's energy needs and reduce CO2 emissions by about 67 per cent, but in the long term the technology will become even more efficient, depending on how high temperatures can be achieved, " Monika Ignatowicz says.

Powerful energy efficiency

The steel, chemical and food industries are examples of production that relies on high-temperature heating. At present, it is possible to reach about 150 degrees.

"But in the long term we hope to reach 260-400 degrees and a very high level of energy efficiency," .

Another advantage of the technology is that you can take waste heat from one building or industry and reuse it in another.

"Yes, it's about being able to integrate different energy systems and finding ways to trick the system so that you can recover energy and reuse it at a local level - connecting a supermarket to a residential building, for example."

However, there are several challenges for HTHP technology. One is ensuring that refrigerants such as ammonia, carbon dioxide and others can be used in a safe and environmentally friendly way, and the initial investment costs are significantly higher than for conventional heating systems. Energy storage is another issue that could become increasingly important in the long term.

Important in the transition

"We are in dialogue with industry and there is a lot of interest in HTHP and how we can use the technology in existing systems in the future,' says Monika Ignatowitcz, who notes that a complex transition of energy systems is a long process. But instruments such as a carbon tax can also speed up the process, where many other EU countries are lagging far behind Sweden."

Monika Ignatowitcz leads the way up a steel-clad spiral staircase to the laboratory where her HTHP prototype is located. It's the first of its kind - built at a university and big enough to heat and cool a house, so she can test the technology in different areas.

"It's important to test, adapt and then take the next step. In five to ten years' time, HTHP will be an important part of the transition," Monika Ignatowicz says.

Text and photo: Jill Klackenberg