“Healthcare and welfare services should be accessible to everyone”

Rustam Nabiev, the recipient of the KTH Innovation Award for 2021, grew up in the shadow of civil war in Tajikistan.

When he was 12-years old, he supported his family by collecting PET bottles. Today, his company facilitates functioning healthcare and welfare services for people living in areas where there is no phone and internet connectivity or roads.

In 1992, civil war broke out in Tajikistan and Rustam Nabiev’s parents fled to the north of the country with their children.

“My dad was a doctor but was very poorly paid and my mum looked after my younger siblings, so I took it upon myself to help with the family finances,” he says.

Nabiev began his early career path by washing cars outside a hotel, until the day a competing gang of older boys outmuscled him and put a stop to that enterprise.

“I then discovered that an acquaintance in a neighbouring town was making a living by collecting loads and loads of empty PET bottles and claiming the deposit on them. I offered to go from door to door in my area after school asking for empty PET bottles, that I then sold on to him, and we both made a decent profit,” Nabiev says.

Sometime later as a teenager, he was queuing on behalf of his family for milk and bread distributed by an aid organisation and was outraged by what he witnessed. They always closed the hatch on the truck at a certain time of day, even if some people were still waiting in the queue outside.

“They said they had run out of stuff, but later in the afternoon, I saw the same truck parked in the market where they were selling the food that was left. I thought, ‘how hard can it be to create systems where people take responsibility for what they give and take?’. All societies need controlled processes to enable people to get help.”

When Nabiev’s youngest sibling was three, his mum started her own business, and asked him to stop collecting bottles and focus on his schoolwork instead.

“But my business was profitable, so I selected a few enterprising class mates who wanted to earn some money of their own. Suddenly, I had about ten boys collecting PET bottles for me. But mum got fed up with the cellar at home always being full of empty PET bottles, and put a stop to it, so I handed the enterprise to a class mate and got stuck into my studies properly.”

When he was 18, Nabiev left the country to study computer science in Germany before applying to Sweden and KTH to study for a master’s degree.

“I studied digital solutions for healthcare, worked as a research assistant and did field work in Africa. I came to realise that I wanted to make primary care more efficient and accessible to everyone in the low-income countries, and became involved in founding Shifo,” he says.

Read more about KTH Innovation Award

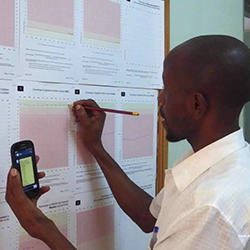

To get the logistics to work in locations around the world where there were no telephone and internet connectivity or roads, Shifo uses its own innovation, Smart Paper Technology, that with the aid of a paper form, saves 96 percent of the time otherwise spent on administration in maternity clinics. In the case of vaccination centres, the technology saves 72 percent of the time personnel need for paperwork.

Health workers bring the form from the rural clinic to towns, where it is scanned and digitalised. Shifo’s solution is described as a “hybrid solution of a paper and data product for primary care and healthcare”.

“Our employees enable healthcare personnel to register each baby born in a village quickly and efficiently, and the time saved also allows for more preventative healthcare, for instance, personnel have more time to offer dietary advice to parents”, he says.

“Primary healthcare in the low-income countries must become more efficient. Care personnel out in the field are forced to spend what could be valuable patient time on inefficient administration, and we aim to simplify the process,” Nabiev says. “We want to save more lives.”

Katarina Ahlfort

Photo: Fredrik Persson