This was a summer to remember! Swedes are normally not spoilt with sunshine and we know how to complain about too much rain and too many mosquitoes. But this year most of us got more than we bargained for. July was extraordinarily hot and dry, it shows on satellite images. Major Tom agrees from his spaceship; Sweden has turned dry and brown.

The weather is always unpredictable, some may say, and next year we could find ourselves back in umbrella and long-john mode. This may be true in the short run. But this summer has shown us a glimpse, and a very hands-on experience, of the future. Climatologists, scientists and well-known weathermen like Pär Holmgren left no trace of a doubt: the stable ‘heat dome’ over Sweden (värmekupol) was linked to the ongoing process of global warming.

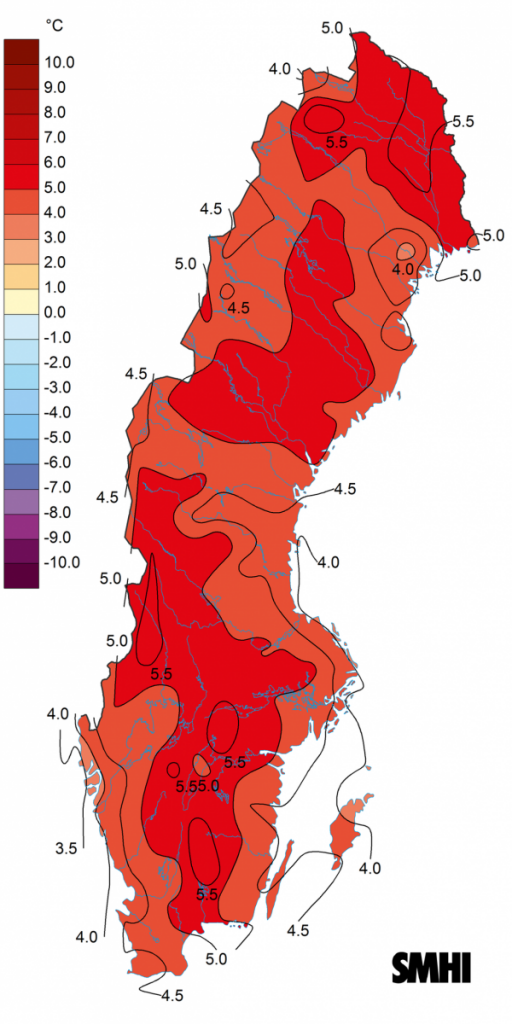

Very recently, researchers linked to the Stockholm Resilience Centre warned about the jittery behaviour of our climate. Some rather complex interactions between the atmosphere, the land masses and our oceans may create “tipping elements” in the planet’s temperature. We may therefore – the researchers suggest – be heading for a faster warming than earlier predicted; towards a permanent ”hot house” of 4-5 degrees above the pre-industrial mean temperature. As a matter of coincidence, this was exactly the temperature rise recorded in Sweden during the month of July, compared to the long-term average.

What we have seen this summer is most likely a first serving of what is to come. Thanks to this extreme summer, we can also start to grasp the consequences of a warmer world also in Sweden. And I’m not thinking about how to chill our bag-in-box-rosé on the beach.

Wild fires have spread across Sweden, at a scale never witnessed before. Tens of thousands of hectares of forest land have gone up in smoke, with inhabitants of entire villages having to flee. Our “arctic wildfires” made headlines all over the world. This said, ours were nothing compared to the massive wildfires still raging in California or the fires in Greece that left almost a hundred people dead.

The Swedish agriculture has taken a huge blow; with crops devastated in large parts of the country and livestock being sent to slaughter as the feed supply dries up. Swedish agriculture is largely rain fed with rather small acreage under irrigation. So when there is no rain, there is no crop. Farmers with irrigation installations have in some places been barred from using them due to water scarcity.

The groundwater levels in small reservoirs have been low or very low throughout Sweden which has not only created problems for the agriculture, but also for municipal drinking water supply. This year, over 100 municipalities introduced irrigation bans or other measures to save on the drinking water supplies. Even Stockholm, drawing water from the huge basin of Lake Mälaren, noted capacity problems as people were filling up their swimming pools and watering lawns in the early summer months. On the national level, the agency Livsmedelsverket has issued recommendations for water saving, and the drought has been a real test for national crisis coordination. As if this was not enough, the national food agency warned that the warm weather can increase the risk for cyanobacteria, adding water quality risks to the shortage of supply.

All these “new “ water-related problems of 2018 almost made me forget the “old” climate challenges. We still have to deal with increased flood events due to heavy rainstorms, and with the sea level rise.

All doom and gloom? At least we can give the Swedish Environmental Protection agency right. In a 2016 report, the agency predicted that climate change will pose serious challenges to our current conventional water infrastructure.

In some ways, we should be thankful for this summer. It was a wormhole in the time warp; an exclusive pre-screening of a not very distant future. It is also a necessary wake-up call. We need to get serious about reducing our greenhouse gas emissions. For water management, the summer of ’18 tells us that “business as usual” will not be an option. On the whole, water will become more rare, unpredictable and expensive, and our infrastructure will have to follow new design principles. Designs that are more resilient and less wasteful. Designs that promote the principles of reduce and re-use; designs that don’t presuppose that we mix our precious water with human faeces. Designs for a warm, but also sustainable, future society.

Fold up your sleeves. Welcome back to work!

David Nilsson

Director, WaterCentre@KTH

Algae blooms have been present in the Baltic Sea for a long time, but they have not always been a regular feature in the broader cultural and social imaginations that exist in and around the Baltic Sea Catchment Basin. That people in Sweden know and care about algae blooms today partially stems from the foundation of HELCOM (an intergovernmental organization tasked with protecting the Baltic Sea) in 1974 and the large algae blooms of 1988. Of course, earlier algae blooms have also been important, including blooms from around the 1920s or 30s that caused an illness reportedly known as Haff-sjukan.

Algae blooms have been present in the Baltic Sea for a long time, but they have not always been a regular feature in the broader cultural and social imaginations that exist in and around the Baltic Sea Catchment Basin. That people in Sweden know and care about algae blooms today partially stems from the foundation of HELCOM (an intergovernmental organization tasked with protecting the Baltic Sea) in 1974 and the large algae blooms of 1988. Of course, earlier algae blooms have also been important, including blooms from around the 1920s or 30s that caused an illness reportedly known as Haff-sjukan.