If recovery of water and heat becomes a standard technology, does it mean a net benefit or cost to society? Who will be the losers, and who will be winners? In the project “SEQWENS” coordinated by WaterCentre@KTH we are looking at exactly this.

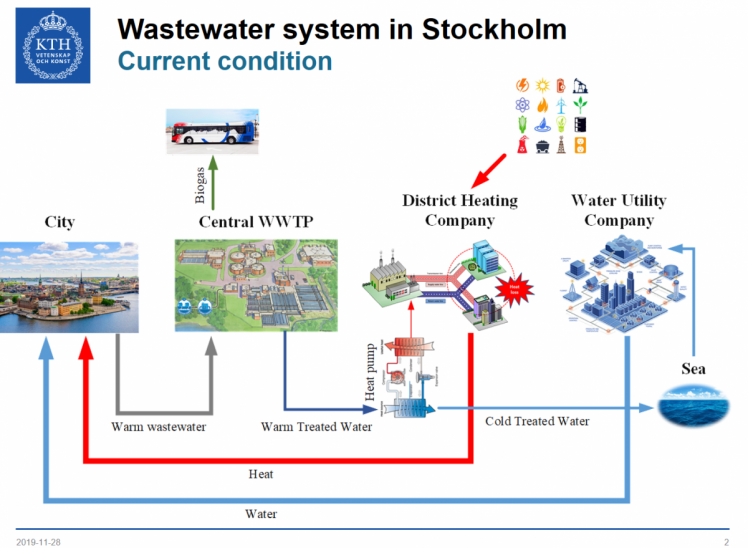

Throughout cities in Europe and the US, the heat in our buildings is distributed by district heating. Over 90% of multi-household properties in Sweden are connected. The property companies buy heat from the district heating grid to warm up cold water (which typically is between 4-15 degrees Celsius), to produce hot water for cleaning, washing, etc. After all, few people enjoy taking a shower in 4 degrees. After use, the hot water is released to the sewerage network leading to a wastewater treatment plant. There it is purified from environmentally harmful pollutants, while the heat is extracted using heat pumps and fed back to the district heating grid.

Fig.1 A system description of water, wastewater and heat circulation today in Stockholm region. (Courtesy of Farzin Golzar.)

As property owners and developers now seek to reduce their energy consumption in pursuit of efficiency targets and GHG emission reduction, they increasingly install technologies for recovering heat from the wastewater on the property. Some also experiment with re-use of the hot water itself, by adding a small-scale treatment stage. Energy for hot water is a substantial share of the total energy consumption. There is energy – and therefore money – to save on wastewater heat recovery.

But what happens to the district heating system then, when less energy is in circulation? Around 800 GWh is extracted annually from the sewage treatment plants by Stockholm Exergi AB, the district heating company covering the Stockholm region. That is no small amount of energy. Moreover, the wastewater released from buildings with heat recovery is going to be colder. Potentially this can cause trouble downstream for the wastewater plant, whose treatment processes will be negatively affected if the incoming water is too cold. So what seems like a great idea for the property owners could be a loss for the district heating company and the wastewater company, both with municipal ownership. If recovery of water and heat becomes a standard technology, does it mean a net benefit or cost to society? Who will be the losers, and who stand to gain from such a development? In the project “SEQWENS” (Sustainability and EQuality of Water and ENergy Systems during actor-driven disruptive innovation) which is financed by FORMAS, we are looking at these questions during 2019-2021.

On 28 November we organised a Reference Group meeting at KTH where we presented preliminary results from our case studies, and discussed the various scenarios we intend to analyse, with representatives from real estate and property, water and heat industry. Dr. Jörgen Wallin, KTH Energy technology, presented the findings from four analyses of existing heat recovery in Stockholm. They represent both commercial and residential houses, and different types of technologies (heat exchangers, with or without heat pump). The test results show that the performance differs substantially depending on the design and operational conditions. One configuration recovers over 40% of the heat available in the wastewater. Regarding the share of recovered heat compared to the total water heating demand, figures over 20% were common.

Fig 2. Reference group visits the heat exchange installation at KTH Live-in-Lab and Einar Mattsson AB property, one of the case studies (KTH Rocks). Photo: David Nilsson

We can confidently say there are substantial energy savings to be made for the property owner, although we are yet to make the economic analysis of these case studies. As one of the property owners put it; the tariff of the district heating service is critical for any investment decision into recovery technology. And from the system-level point of view, the overall outcome of individual actors’ strategies still needs to be assessed. Is the new technology a saviour or saboteur for sustainable development in society? Or just something in between?

In the coming year, the project will focus more on the analysis of actor strategies, and a case study on organisational innovation in Värmdö municipality. We will also start building scenarios that can be evaluated using a conceptual model for heat and water circulation in Stockholm. This work is led by Dr. Timos Karpouzoglou in cooperation with Dr. Farzin Golzar, both KTH, and Associate Professor Pär Blomkvist from Mälardalen Högskola. If your are interested in following our project, please get in touch with the WaterCentre administrator Lisa-Mee Swartz (lmswartz@kth.se) or just visit our project webpage every now and then.

To be continued!

David Nilsson

Director, WaterCentre@KTH

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!