Slow-down, infiltrate, filter. These are the reassuring mantras at the heart of efforts to emulate the drainage patterns of natural systems and a practical strategy to mitigate the increasingly severe effects of urban flooding. Departing from the traditional hard-surfaced approach of “pave, pipe and pump” this naturalised approach to drainage represents the blue strand in the budding concept of “Green Infrastructure” (GI) which weaves together stormwater management, landscape, ecology, air quality, climate change adaptation, public health and recreation in the urban setting.

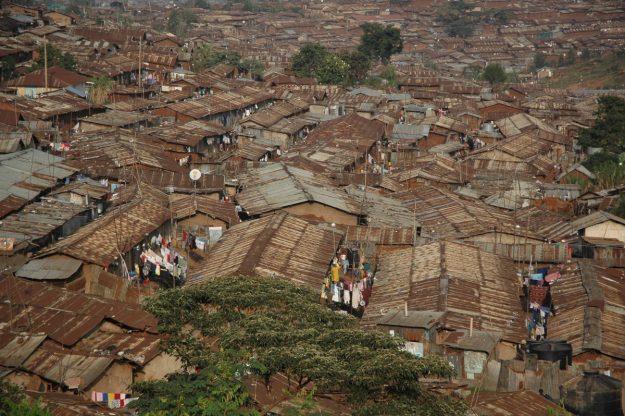

All infrastructure development requires significant space and careful planning. Green infrastructure even more so, as water is encouraged to slow, stop, infiltrate and evaporate where it falls. At the same time, the intensity of severe rainfall events is rising in many regions, requiring more space to deal with ever-increasing flows. So what does sustainable drainage and green infrastructure mean in different cities, especially for rapidly growing cities like Nairobi, Kampala or Lagos where the majority of new urban residents will live in low-income, dense and “informal” neighbourhoods where there is little space?

Many cities rightly feted for their achievements in Green Infrastructure – for example Portland, Melbourne, or Stockholm – represent different geographies. But they are also typically wet and temperate, well-resourced, and well-coordinated. Not seldom are they re-generating underutilised spaces when implementing GI approaches (e.g. Hammarby Sjöstad). Other successful strategies make use of new opportunities created by the vacation of previously occupied land (e.g. in legacy cities like Detroit).

Image: Hammarby Sjöstad (Mikael Sjöberg/mediabank.visitstockholm.com). Top Image: Kibera rooftops (Joe Mulligan).

Image: Green Infrastructure development in the Cody Rouge area of Detroit (Joe Mulligan)

Green Infrastructure in the East African city: a pipe-dream?

In the rapidly growing cities where we are working in East Africa the catch-all concept of Green Infrastructure could have significant co-benefits, but also faces some knotty challenges. In many cities the public land along natural drainage paths is inhabited by the city’s poorest and most vulnerable (see for example Parikh et al, 2012); residents’ solution to a lack of affordable housing. The density, imperviousness and lack of sanitation services in these settlements create hotspots of flooding and public health risks while leaving little physical or political space to manoeuvre. Divisive planning regulation, sometimes stuck in the colonial era, increasingly intense extreme rainfall events, and the appropriation of green space into dense developments through both “formal” and “informal” processes compound the physical and social problems.

Video: flash flooding after 15 minutes rain in Andolo, Kibera (Pascal Kipkemboi)

A discussion on the potential and constraints of GI in rapidly growing cities is now timely with new investments in the networked and stacked infrastructures of roads, drainage, water and sewerage, as well as more holistic approaches to “slum-upgrading”, being planned in many cities. At the same time there is the risk of locking-in unsustainable practices and long-life infrastructures. In Nairobi, today there is concern that the proposed city-wide Stormwater Masterplan will encourage traditional hard drainage solutions that don’t activate the potential of green and open spaces and that are inflexible to future climate change.

Site, Settlement, Watershed – Networking Green Infrastructure from the Bottom-Up

As major upgrading works take time to plan and implement we also need to think about interim improvements to reduce daily risks for residents. In our work at KDI we have been piloting a number of sustainable drainage techniques in the Kibera neighbourhood of Nairobi at the very local scale. In practical terms, these include GI elements such as planted revetments, bamboo plantation for erosion control, structured detention and infiltration (using soft drink crates instead of expensive “stormblocs”) and rainwater harvesting. Even when harder drainage solutions are the only spatially viable solution, there are opportunities to improve public health, access and safety, and to create green, open and productive public space for social interactions, play and economic activity.

Image: Green Infrastructure and Public Space at the small scale in the Kibera settlement (Joe Mulligan/Pascal Kipkemboi)

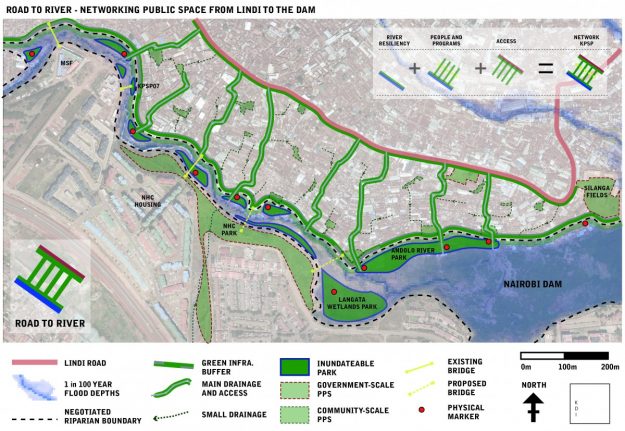

At the larger scale Green Infrastructure in dense urban areas implies some unavoidable trade-offs. The question is; can residents and local authorities come together to discuss acceptable levels of risk and negotiate appropriate re-housing while creating space for social and ecological functions? The success of enumeration and participation processes in Kibera run by intermediaries such as Slum Dwellers International and Akiba Mashinani Trust (see Mitra et al, 2017) suggest this could be possible. If layers of local knowledge, scientific understanding of flooding, appropriate re-housing and integrated planning can be combined with green infrastructure as an organising framework, the co-benefits of ecological remediation, climate change adaptation, improved services and local development opportunities could be realised. That’s a lot to factor in, but demonstrating that GI techniques can actually work in dense, urban and low-income areas at the small scale might be a starting point for inserting them into larger discussions.

Image: A conceptual “Rivers and People” plan by KDI in 2016 for the co-development and rehabilitation of the Ngong River in Kibera.

Joe Mulligan, is a civil and environmental engineer and associate director of KDI working on water and drainage strategies in multiple contexts for more than ten years. He is also an industrial PhD student at KTH Division of Strategic Sustainability Studies.

Vera Bukachi is a civil engineer and the senior research coordinator in KDI’s office in Nairobi and is completing a PhD at University College London’s Centre for Urban Sustainability and Resilience where she has also taught urban drainage and flooding.