Aliaksandr Piahanau and Per Högselius are organising an online workshop based at our division at KTH on 1 February 2023. Our colleagues are inviting scholars from around the world to discuss the “European Energy Shortages during the Short Coal Age (1869-1960)”. Of course, the workshop hits the zeitgeist, as current rearranging energy systems take discussions about fossil energy shortages in Europe to the forefront of the public discourse. Below you find the call for papers both as text and as a PDF for download. Please consider applying!

*

Call for Papers for an online workshop at KTH Royal Institute of Technology

European Energy Shortages during the Short Coal Age

(1860-1960)

Date: 1 February 2023

Format: online

Objective: a workshop with the intention to produce a special issue or an edited volume

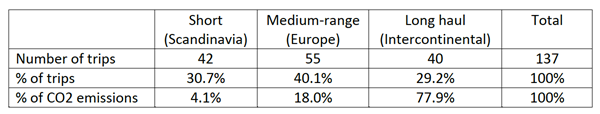

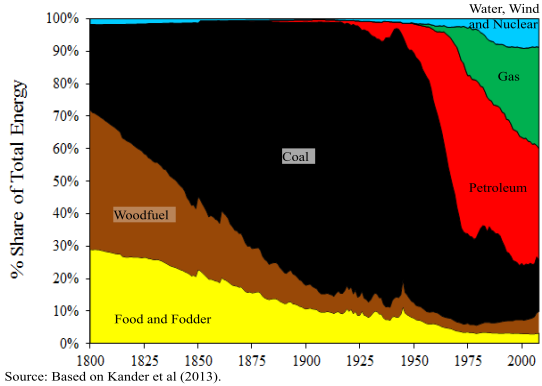

The winter of 2022-2023 in Europe may become the harshest since 1944 due to fuel and electricity scarcity. This is an obvious moment for revisiting historical energy shortages. The proposed workshop will target the period of repeated fuel shortages in Europe from roughly 1860 to 1960 – the century during which coal dominated European energy supply. Throughout this period coal supplied more than 50 % of all energy (figure 1).

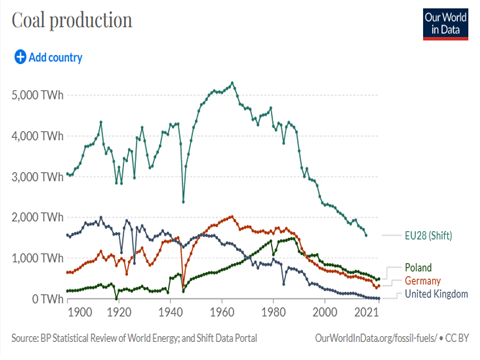

Coal’s supremacy in the European energy balance peaked around the First World War. This dominance was enabled by a small group of leading coal producers: Britain, Germany, and, later, Poland, which exported the fuel to a range of other countries in Europe and beyond. British coal production peaked in 1913 (at nearly 300 million tons) and the number of coal miners reached its maximum in 1919 (at over 1 million). The peak was followed by rapid decline. Germany and other coal-producing countries went down the same path later on. For Europe as a whole, however, coal consumption peaked only in the 1960s (figure 2), after which coal lost its dominant position to oil and gas in relative terms as well. From the 1960s, the European coal consumption entered a lengthy period of decline. We propose to label the period during which coal dominated European energy use – from around 1860 to 1960 – “the Short Coal Age,” challenging the more commonly used periodization in the focus is traditionally on the (Long) Coal Age and its links with the Industrial Revolution and the Age of Steam.

Long-term data on coal consumption and prices show big fluctuations in European coal markets, especially in the first half of the twentieth century. High demand frequently encountered low supply, creating a classical “shortage” situation. Some of the mismatches between demand and supply had disastrous consequences for Europe, as reflected in contemporary public discussions (figure 3). Yet energy historians have so far not addressed the nature of European coal shortages sufficiently. In both scholarly and recent public debates historical coal shortages remain largely overshadowed by the oil shocks of the 1970s. Only a few studies have examined coal scarcity (see, for example, Weiller 1940; Lemenorel 1981; Mayer 1988; Kapstein 1990; Izmestieva 1998; Triebel 2009; Chancerel 2012; Mathis 2018).

This gap calls for interdisciplinary and international research cooperation in order to assess the story of long-term energy shortages in Europe. The participants of the planned workshop are invited to reflect together upon coal shortages, their manifold faces and outcomes, during the centenarian apogee of King Coal’s rule in Europe. The workshop aims to bring together researchers with different disciplinary backgrounds, such as history, energy studies, international relations, the technological and environmental humanities, geography, economics, media studies and anthropology.

We propose to structure the workshop around three theoretical angles. The first angle is the discursive understanding of the shortage phenomena; the second relates to their temporal dynamics; the third concerns their spatial (and geopolitical) effects.

By the discursive angle we mean narratives, arguments and ideas provoked by questions like – what happens when our massive flow of cheap energy suddenly disappears? The British intellectual William S. Jevons warned in his Coal Question (1865) that the coal dependence will menace modern society in near future. Jevons feared that the approaching coal depletion would ruin the industrial way of life in Britain and its international position. Reflecting upon the ideas of scarcity in an industrialised economy, British English coined the term “shortage” as a synonym for “lack” and “scarcity” (used for the first time in 1868). For the next hundred years, this term became primarily used in relation to the lack of labour and of coal. In a retrospective analysis, historians confirmed the importance of shortages for the modern development. On the one hand, coal shortages (and price peaks) pushed energy transition, promoting oil, water power and gas technologies (Fouquet 2016). On the other hand, the ability to stop the coal distribution tremendously empowered modern workers. As Mitchell (2011) famously argued in Carbon Democracy, by menacing or performing “energy sabotage” by acting in the checkpoints of the fossil-fuel-based economy such as mines, railways and ports, coal professionals were able to secure more rights and freedom than any time before. We are interested in deepening this reflection by asking what kind of fears and hopes, challenges and opportunities, coal and its shortages provoked in different contexts.

Our second theoretical focus is chronological. The uncommon time-frame of 1860-1960 as a single European period offers a possibility to check the long-term patterns where researchers usually look for the discontinuity associated with the two world wars. The focus also reveals that the “Short Coal Age” was a paradoxical period from another point of view. The relative coal abundance between 1860 and 1960 was also perforated by repeated moments of drastic energy scarcity. Ethan B. Kapstein, for example, argued that the late World War II coal shortage in Europe was “the most devastating energy crisis in its modern history” (1990, 17). However, the coal undersupply of 1917-21, which occurred at the peak of European coal dependence, seems to have been even more serious. Smaller coal shortages struck in 1873-4, 1899-1903, 1926 and 1956. This uneven spread of coal shortages, which occurred in times of both peace and war, is another fascinating subject, and we aim to develop a chronological mapping of coal shortages in Europe.

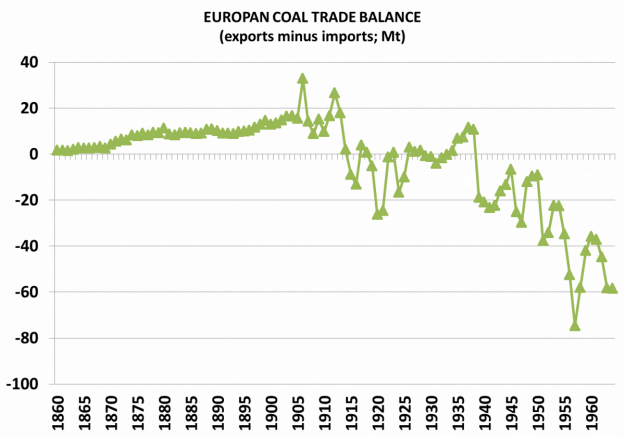

Our third point targets the spatial dimension. Coal supply and its shortages affected different areas in varying degree and unevenly sparked both international competition and cooperation. By accident or not, the “Short Coal Age” in Europe was also a period of intense international confrontations and warfare. The half-century before 1914, when coal was exported in big volumes out of Europe, were the heydays of European imperialism in Africa and Asia. Coal exports assured British domination over the oceans through establishment of coaling stations, which led On Barak to propose the term “coalonialism” (2021). But since 1914, Europe cut its overseas coal exports, increasingly becoming a net coal importing region (figure 4). The two world wars demonstrated that modern total warfare was a kind of state-run competition of endurance, where home-front economy was as important as frontline combat. Military campaign devoured giant portions of energy and its success was largely defined by the amount of coal which one side could mobilize (Tooze 2007). The world wars brought new territorial rearrangements over important coal areas (such as Alsace-Lorraine, the Saar, and Silesia), but also sped up an international cooperation in coal supply on the European level. The Versailles conference of 1919-20 formalised a first international system of coal exchange, which was included in peace treaties (Soutou 1989). Dealing with the ruinous coal shortages, the winning coalitions established the European Coal Commission in 1919 (which later was integrated into the Economic Commission of the League of Nations), and the European Coal Organisation in 1945, later replaced by the much more powerful (and successful) European Community of Coal and Steel in 1951. The transition to an oil-and-gas economy in the 1960s not only freed Europe from the dictate of the coal mining industry, but also, possibly, left international conflicts over coalfields to the past – at least until 2014, when war broke out in Eastern Europe’s chief coal mining centre, located in Ukraine’s Donbass region.

Most of all, we are interested in studies on coal supply breakdowns and how they affected European coal dependent actors, such as importing countries, industries and urban communities. International organisations or summits, dealing with coal shortages, are also relevant cases. Comparative studies juxtaposing different geographical, temporal or social cases, are particularly welcomed.

Researchers are invited to discuss one of the following topics:

Dynamics. What were the agents and structural forces underlying particular coal shortages? How did the coal shortages directly affect actors and society?

Adaptations. Which strategies were considered and tested in order to improve the energy situation and/or overcome the crisis? What were the short- and long-term results?

Wider impact. Which changes did coal shortages bring in power, economy and social structures? Who were the winners and losers, who was not affected and why? What kind of challenges and opportunities did coal shortages create? How was the European environment affected by energy shortages and attempts to overcome it?

Revelations. How did people understand coal shortages in broader sense? Were coal shortages integrated into a particular narrative or political discourse? To what extent did these shortages affect the dominant ideological assumptions?

Expectations. How did actors and society forecast future coal supply? Which measures were taken in order to avoid new shortages? How effective were these measures during coal shortages?

The workshop is planned to be held online on 1 February 2023. Interested researchers are invited to submit a paper proposal (up to 500 words) and a short bio to Aliaksandr Piahanau (piahanau@gmail.com) by 15 November 2022. Selected speakers will then be asked to submit full papers (up to 8,000 words including references) by 15 January 2022. After the workshop, we hope to turn its papers into a special issue for a major peer-reviewed academic journal, or, alternatively, into an edited volume.

Organisers: Aliaksandr Piahanau, postdoc researcher in energy history (piahanau@gmail.com) and Per Högselius, professor of history of technology (perho@kth.se), KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Text by

Text by  The workshop included presentations with experiences from Portugal and Sweden on nature-based solutions and green buffer zones in response to climate changes and risks of flooding.

The workshop included presentations with experiences from Portugal and Sweden on nature-based solutions and green buffer zones in response to climate changes and risks of flooding.