A warm welcome to another upcoming final seminar at the division!

Doctoral Student: Siegfried Evens, Doctoral Student, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment

Supervisor: Per Högselius, Kati Lindström, Anna Storm

Opponent: Markku Lehtonen, Social Scientist, University Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona

Time: Tuesday 2023-06-13 13.15 – 15.00

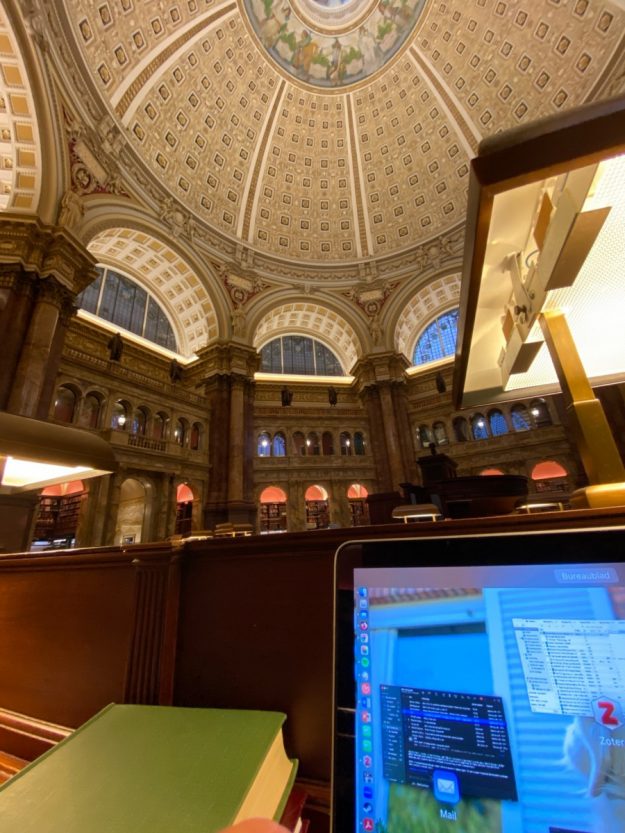

Location: Big seminar room, Teknikringen 74D (floor 5), Division of History of Science

Language: English

Teaser

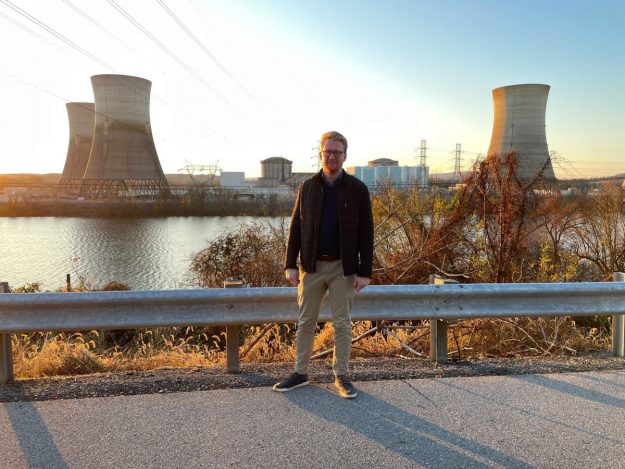

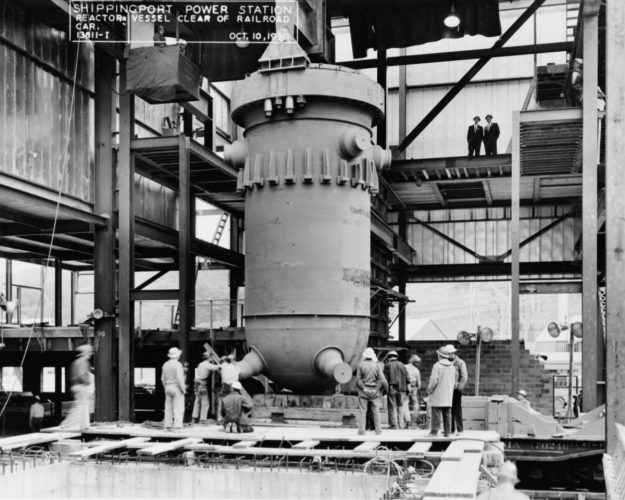

That is why this dissertation will focus on exactly that: the water that runs through our nuclear power plants. Water is so important and obvious to the safety of so many power plants – not only nuclear ones – that it barely goes unnoticed. Indeed, the history of nuclear power contains a striking paradox. Water is the key to a normal functioning nuclear power plant and to preventing nuclear accidents. Yet, up until now, the history of water is largely absent from the history of nuclear power, and especially nuclear risk. In contrast, there is a long–standing scholarly tradition of studying nuclear fission and radioactivity.

But this dissertation is about more than just water. By focussing on water streams for the analysis of nuclear safety, other relevant elements open up as well. While water streams are essential, there is no nuclear power plant in the world that generates electricity because of it. Electricity is generated because of the steam caused by the boiling of that water. The generation of steam is coupled to the science and engineering practice of thermal–hydraulics – a field with a long and important history, dating back to the early days of industrialisation and mechanical engineering.

As I will show, much engineering and political effort – in the nuclear sector and outside of it – has been devoted to the management of pressure and temperature in steam equipment, such as boilers and pipes. All of this was essential to prevent the pressure from mounting too high, causing catastrophic explosions. In turn, the management of all this water and steam is also very reliant on the material that this equipment is made of. And that material is steel. A very robust material, steel is well–equipped to

withstand the tremendous pressures and temperatures necessary to generate power. However, as with almost any material, it can decay, crack, brittle, and break. A major theme in this dissertation will therefore be the continued effort to improve and regulate steel – and the work of metallurgists and material engineers in doing so. Streams, steams, and steels; that is in many ways the essence of

this dissertation.

Excerpt from Siegfried’s final seminar text, pp. 12-13.

Eglė Rindzevičiūtė is an Associate Professor of Criminology and Sociology, Kingston University London, with an interest in governance, knowledge production and culture. Her Friday talk with us is based on the forthcoming book, The Will to Predict: Orchestrating the Future through Science (Cornell 2023).

Eglė Rindzevičiūtė is an Associate Professor of Criminology and Sociology, Kingston University London, with an interest in governance, knowledge production and culture. Her Friday talk with us is based on the forthcoming book, The Will to Predict: Orchestrating the Future through Science (Cornell 2023). What is good drinking water?: 41 Years of risk perception on water quality in the vicinity of the Nuclear Research Centre Karlsruhe, 1956–1997

What is good drinking water?: 41 Years of risk perception on water quality in the vicinity of the Nuclear Research Centre Karlsruhe, 1956–1997