Gott nytt år! – Happy New Year! After snow-induced Christmas and winter holidays, the division is slowly but surely bustling back into busy work mode.

Our Higher Seminar Series, the colloquium of our division, starts again in two weeks. We are very glad to announce that Aliaksandr Piahanau, Wenner-Gren postdoc at the division, will be presenting his ongoing research. His talk “The Great Energy Supply Crisis: Fuels & Politics in Central Europe, 1918–21″ will be given on 24 January at 13.15-14.45 Stockholm time. If you want to join us from outside KTH, please send an email to higher-seminar@kth.se before 10 am (CET) the day you wish to attend.

Abstract

Even a short breakdown in fuel supplies can have profound and dramatic consequences for modern economies. This paper explores a major coal shortage in Central Europe after WW1 which shook local societies for two years. The dissolution of the Habsburg Empire in 1918 provides a narrower context to this study, while its immediate focus lies upon the development of diplomatic and economic relationships between Czechoslovakia – a WW1 winner state and an important coal exporter, and Hungary – a war losing state, which was a net coal importer. Underlining the scale of the Hungarian reliance on fuels from Czechoslovakia, this paper suggests that this dependence was one of the chief arguments that motivated Budapest to cede Slovakia to Prague’s control and, in general, to accept the peace terms proposed at the Paris conference. The paper demonstrates that cross-border energy interdependence substantially affected diplomatic relations in Central Europe immediately after WW1, privileging coal-exporting states over coal-importing states.

Apart from this exciting talk focussed on the subject of Eastern Central European History, many more presentations are coming up. Here is the current schedule:

24 January 13.15-14.45 CET: The Great Energy Supply Crisis: Fuels & Politics in Central Europe, 1918–21. Aliaksandr Piahanau, Wenner-Gren postdoc, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment

7 February 13.15-14.45 CET: PM for PhD project. Erik Ljungberg, doctoral student, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment

21 February 13.15-14.45 CET: Air Epistemologies: Practices of Ecopoetry in Ibero-American Atmospheres. Nuno Marques, postdoc, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment

7 March 13.15-14.45 CET: From modern to modest imaginary? Learning about urban water infrastructure by comparing Northern and Southern cities. Timos Karpouzoglou, researcher, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment. Collaborators in this work: Mary Lawhon, Sumit Vij, Pär Blomqvist, David Nilsson, Katarina Larsen.

21 March 13.15-14.45 CET: Warriors, wizards, and seers: representations of Saami in 17th and 18th century Sweden. Vincent Roy-Di Piazza, Oxford Centre for the History of Science, Medicine and Technology, University of Oxford, UK

4 April 13.15-14.45 CET: Historian’s toolbox: Technical solutions for doing research. Kati Lindström and Anja Moun Rieser, Division of History of Science, technology and Environment

2 May 13.15-14.45 CET: Mid-seminar in doctoral education. Gloria Samosir, doctoral student, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment

16 May 13.15-14.45 CET: Nuclear Nordics: Histories of Radioactive Waste in the Nordic Region. Melina Antonia Buns, visiting postdoc KTH

30 May 13.15-14.45 CET: A theoretical seminar on Heritage and Decay. Lize-Marie Van Der Watt, researcher, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment

13 June 13.15-14.45 CET: Science, the arts and engineering – dialogues and co-creative methods between KTH and Färgfabriken. Katarina Larsen and David Nilsson, researchers, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment

You can find the full and always updated Higher Seminar schedule here.

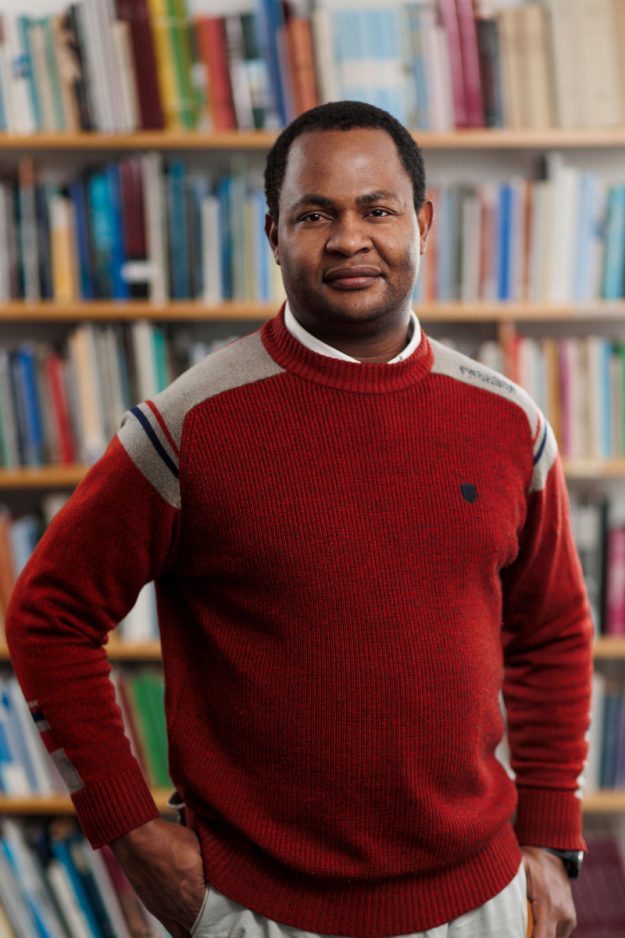

Doctoral student: Domingos Langa

Doctoral student: Domingos Langa

Over the past two years, these plants have breathed with us, and the humming of the pump and the dripping along the chains have filled the pauses in our conversations over lunch. The first attempt was a mediocre success: a few plants (basil and lemon balm) died almost immediately; the ivy and coffee plants fared much better, but eventually succumbed to systemic problems. The nutrient solution evaporated too quickly – we added plastic pipes along the chains to minimise splashing, but this did not fix the problem – eventually causing the system to clog up completely.

Over the past two years, these plants have breathed with us, and the humming of the pump and the dripping along the chains have filled the pauses in our conversations over lunch. The first attempt was a mediocre success: a few plants (basil and lemon balm) died almost immediately; the ivy and coffee plants fared much better, but eventually succumbed to systemic problems. The nutrient solution evaporated too quickly – we added plastic pipes along the chains to minimise splashing, but this did not fix the problem – eventually causing the system to clog up completely.

Fredrik Bertilsson came to the Division of History of Technology, Science, and Environment in 2018. His main research focus is within the area of knowledge management and research policy.

Fredrik Bertilsson came to the Division of History of Technology, Science, and Environment in 2018. His main research focus is within the area of knowledge management and research policy.