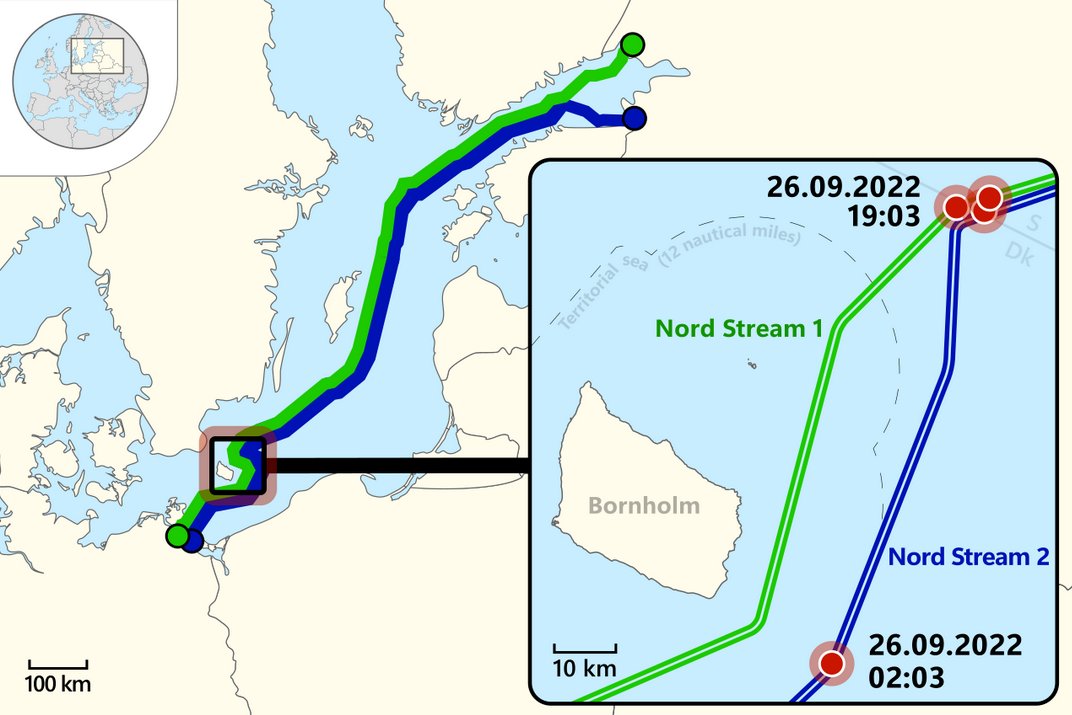

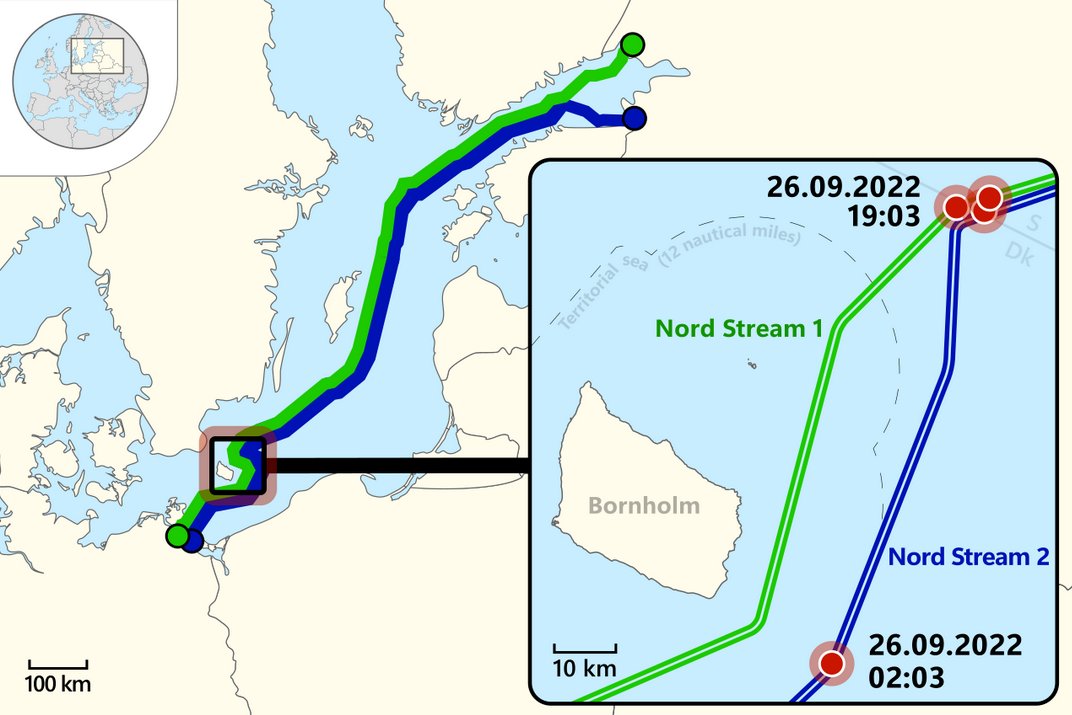

In summer 2011 laying of the first Nord Stream 1 pipe was completed. Italian pipe-laying vessels did the job. The second of the two Nord Stream 1 pipes followed a year later.

• • •

In summer 2011 laying of the first Nord Stream 1 pipe was completed. Italian pipe-laying vessels did the job. The second of the two Nord Stream 1 pipes followed a year later.

• • •

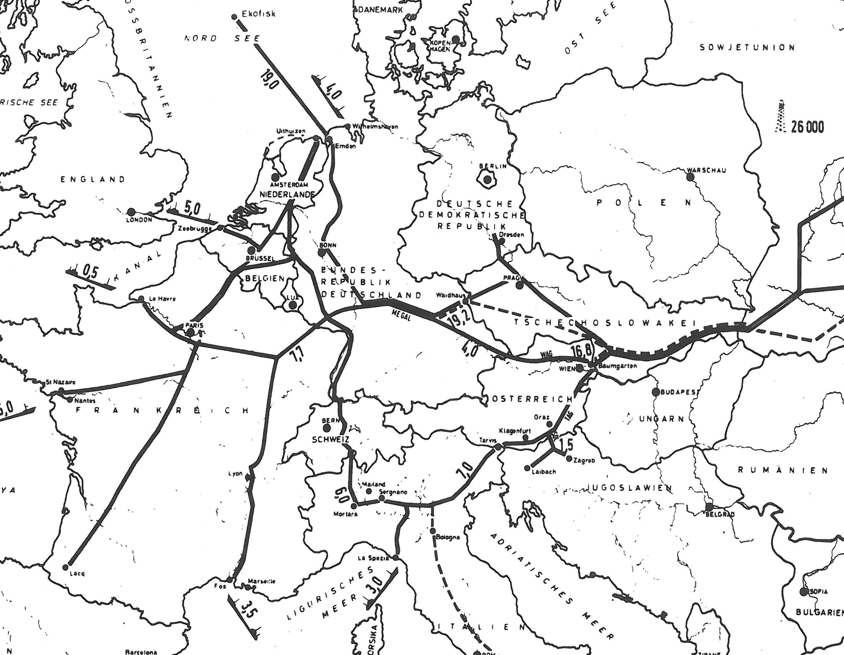

1. From Kaliningrad to Denmark and Britain (found feasible in a 1992 study)

2. From Finland to Germany (found feasible in a 1997 study)

3. Directly from the St. Petersburg area to Germany

• • •

Stay tuned for the second thread, published as a full text next Monday (October 24)!

Full text with references: Vår bild av savannen avslöjar vilka vi är

Already 60 years before Christ, the Roman poet Lucretius speculated whether the first humans were of stronger stuff than the spoiled civilized equivalent, and in the 18th century, the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau expressed a similar idea, contrasting an idealized image of a harmonious state of nature against a corrupt contemporary. However, after World War II, theories about the origin of humankind gained new weight: they were to be substantiated scientifically rather than philosophically.

In the book “Creatures of Cain: The Hunt for Human Nature in Cold War America”, the historian of ideas Erika Lorraine Milam writes a kind of savannah’s cultural history from the end of World War II.

The popular science stories of the 1950s about the origins of humanity emphasized cooperation, everyone’s common roots and the ability to communicate as an essential human trait. They were often cheered on – intellectually and financially – by Huxley’s Unesco. However, as the dream of a harmonious world began to fall and the balance of the cold war terror took over, the mood on the savannah also changed.

60’s pay attention to man’s inherent aggressiveness. A new generation of popular science writers highlighted characteristics such as violence and dominance as defining for the first humans. This inherent aggression had dictated the conditions of existence on the savannah, where those who wanted to survive had to establish a violent capital.

This savannah did not become particularly long-lived. Milam places the end of the idea of The Killer Ape, the dominant male as ruler of the savannah, to the 1980s. Who stepped in and took his place? No one, she answers. “When violence and prejudice became personal,” Milam writes, “biological theories of aggression and human nature became inadequate.” Collective explanatory models lost status and when the Cold War regime began to loosen up, the terrorist balance of our ancestors disappeared. Time had run out from the savannah, free individuals who left the stone axes in the grass and did not want to feel any common prehistory replaced The Killer Ape.

Nevertheless, the cultural history of the savannah does not end here after all. We find it everywhere at the bookstores’ top lists, and in TV productions and radio shows, it is an obvious foundation. Rather than disappearing, the savannah just seems to have changed shape. The prehistory that appears in the health literature appears as a continuation of the ideas that Milam describes in her book, but where the individual is more interesting than the common. Today we do not refer to our ancestors in matters of violence and prejudice, instead they are used to answer questions about how to live a better life. In this way, the savannah retains its moral implications, but not for society at large, but for the individual. Huxley’s vision of society has been replaced by self-optimization.

Swedish epidemiologist Anders Wallensten, author of the book The health mystery (Hälsogåtan: evolution, forskning och 48 konkreta råd, Bonnier Fakta, 2020), presents a savannah where the community is larger and the group’s cohesion is crucial for its continued survival. However, the goal of the community is not, as was the case in the utopian descriptions of the 1950s, a new society, but how individuals, through the support of the community, are to create a good life. Cooperation and community do not appear as goals in themselves, but as means for the individual to realize himself. In addition, the individual’s responsibility seems almost absolute.

Since Julian Huxley stood on the steps in Paris, the inhabitants of the savannah have repeatedly changed shape, and the popular science writers of the future will probably let the savannah be populated by additional new inhabitants, where the props remain but the ensemble is replaced. Perhaps the self-optimizing savannah people will have to make sacrifices for each other when pandemics and climate change hit their contemporary counterparts. Or something completely different happens. Perhaps the most interesting thing is not what answers the savannah can give us, but what questions we think it can answer.

Text: Erik Isberg, doctoral student in the project SPHERE

Full article (open access): The seeds of a European risk society: Marcinelle and the European Coal and Steel Community

Siegfrieds own, terrific summary which you also can find on his Twitter account:

In 1956, a terrible accident with a mine chariot happened in the Bois du Cazier coal mine in Marcinelle, Belgium. 262 miners died, of which 136 Italians. The disaster was in many ways transnational. Casualties came from all over Europe (mostly Italy), but the risks that led up to the disaster were similar in other countries too.

In 1956, a terrible accident with a mine chariot happened in the Bois du Cazier coal mine in Marcinelle, Belgium. 262 miners died, of which 136 Italians. The disaster was in many ways transnational. Casualties came from all over Europe (mostly Italy), but the risks that led up to the disaster were similar in other countries too.

My argument: the European Community of Steel and Coal (ECSC) seized this opportunity to increase its power. In doing so, it laid the foundation of later risk management policies, or what we can call ‘the European risk society’. Marcinelle shaped how the EU deals with risk! EU historians have often argued that the impact of Marcinelle on the ECSC was limited and that ECSC failed in mine safety policy. While it was indeed not their proudest moment, we do not have to be too skeptical either. Yes, a lot of social measures regulating wages, working times, and immigration did not materialise. But a lot of other (more technical) measures did. Understanding the impact of Marcinelle thus means looking at risk management at large. The ECSC went all-in on social policy (still a difficult area for the EU today) and therefore created a (fake) contrast with other technical safety measures. Ironically, it is in the latter category it would be the most successful. Social and technical are hardly separable.

In the article, I follow the developments of a conference on mining safety and the foundation of the Mines Safety Commission. Both were important for internationalising many safety discussions and agenda-setting. They also brought risk assessment into the European institutions. Lastly, we have to analyse Marcinelle long-term. Whether the mines actually became much safer is doubtable. Many mines also closed soon after. But European risk management continued, especially in the Single Market. I even found references to Marcinelle in the Euratom archives.

Otso Kortekangas, postdoc at the division, has written a new book. In “Language, Citizenship, and Sámi Education in the Nordic North, 1900-1940” Otso investigates how Sámi people were affected by nation state education doctrines in Finland’s, Norway’s and Sweden’s North.

One important part of the political context in the genesis of this book is the announcement of the Finnish government to form a Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2019. Its task is to investigate, showcase and discuss injustice and oppression done by the Finnish state towards the Sámi, with the aim of reconciliation and a better future.

Otso presents his book in the following text, first published on McGill-Queen’s University Press’ Blog on 06 May 2021.

The year 2021 will witness the start of the work of a Sámi Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Finland. A TRC is already working in Norway, and in Sweden, the planning for a Sámi TRC is under way. The main aim of the TRCs in each country is to review and assess earlier governmental policies targeting the indigenous Sámi population in Norway, Finland and Sweden, make Sámi voices and experiences visible, and to point toward ways forward.

Differently from the Canadian TRC (2008–2015) that focused on indigenous education and residential schools, the Nordic Sámi TRCs will take a comprehensive approach to historical policies targeting the Sámi and, in the case of Norway, the Finnish-speaking Kven minority. However, governmental educational policies will be a very important theme for the commissions to investigate, as assimilation and segregation applied in education is one of the external forces that have molded Sámi culture the most during the 20th century.

As elucidated in my book Language, Citizenship, and Sámi Education in the Nordic North, 1900-1940 (MQUP 2021), different educational actors had different approaches. Sámi education was traditionally organized by the Lutheran churches in each country. The high priority the Lutheran dogma ascribes to the intelligibility of the gospel and Christianity education by large entailed that Sámi language varieties were in use as languages of instruction in many schools with Sámi pupils in the Nordic north. Gradually, the governments of Norway, Sweden, and Finland took over the responsibility for elementary education from the church around the turn of the century 1900. The governmental educational authorities and politicians downgraded the importance of Sámi language in education, as quality of education and the mastering of each country’s majority language became paramount educational aims. In Norway and Finland, assimilation to the majority population was the norm in the governmental elementary schools, with certain exceptions. The nomadic reindeer herding Sámi in Sweden’s mountain regions were de jure separated to their own group, with the obligation to place their children in specific schools. These so called nomad schools were designed after the idealized notion Swedish elementary authorities had on the “true” Sámi way of life and efficient reindeer herding.

The educational reforms of the early twentieth century that led, in many individual cases, to the tragic loss of Sámi language, had a brighter side, as well. As in many other instances of minority education, the skills and knowledge Sámi pupils gained in the schools had, at least in some cases, an empowering function. Most of the powerhouses spearheading the early and mid-twentieth century Sámi cultural movements and the Sámi opposition to government policies were teachers, educated at schools and on teachers’ training courses to navigate both the Sámi and the majority culture contexts. These teachers were pioneers of promoting Sámi culture as an active, independent culture that existed alongside and independent of other Nordic cultures and states.

While the TRCs in each country are paramount for the future relations of the Sámi and the majority populations, it is important to keep in mind that the Sámi existed and exist also outside of the frame and borders of each of the three nation states. There is a certain risk of nationalization and further minoritization of the Sámi in Norway, Sweden and Finland if the various Sámi groups are always first and foremost treated as a national minority rather than a transnational population. It is critical that this historical transnational fact, together with the diversity of voices and perspectives within Sámi education, are included in the work of the TRCs in each country. Only by so doing will it be possible to reproduce a rightful picture of historical events as a base for future reconciliation processes.

If you are interested in reading more, check out Otso’s book here.

To Northern Europeans, Antarctica is still a place of wonder and mystery. This might even more so be the case in times of rapid climate change – for a plethora of reasons.

The following story happened at Hope Bay in Antarctica. In January 1902, Otto Nordenskjöld together with his Swedish Antarctic Expedition discovered the bay. Unfortunately, their boat sank due to collisions with floating ice and the expedition was forced to spent quite some time at land. The shipwrecked built a stone hut, which provided them with much-needed shelter against the elements. Ultimately, they were rescued by the Argentinian boat “ARA Uruguay” under the command of Julián Irízar and could return home.

The following text is a translation done by our division’s researcher Kati Lindström from Duse’s Amongst Penguins and Seals (Stockholm, Beijers Bokförlagsaktiebolag, 1905, pp. 178-181). Duse was a member of the stranded expedition. The translated text was originally published on the Melting History blog. This blog is part of the project evolving around CHAQ 2020 (Cultural Heritage Antarctica 2020), “an Argentinean-Swedish expedition to the historical remains of the First Swedish Antarctic Expedition 1901-1903 on the Antarctic Peninsula.” Researchers involved with ties to our division are Dag Avango (now Professor of History at Luleå University of Technology), Lize-Marié Hansen van der Watt and Kati Lindström.

—

Samuel Duse writes:

The worst was during the periods of rough weather when we were forced to stay inside the artificial polar darkness of the stone hut, not disturbed by a single ray of light – perhaps only when a heavier storm tore open the ice plaster in the roof. …

We soon learned to predict when the southern storms would hit. Usually, it first started with a quiet snowfall while the barometer sank. When the barometer started to raise again, it was not long before a gust of wind heralded that the dance is starting soon. The newly fallen snow would start to move and it was best to crawl into the stone hut while you could still see something. Here inside you could lay down now and listen to the wild play of the mighty storm. It whispered and roared, it whistled and squeaked, the roof pounded with flying ice bits and small stones. It sounded as if all hell’s demons were trying hard to lay their hands on us here inside.

But the stone hut was sturdy and no storm could pull it down. Despite the brutal cold inside, filthiness and darkness, we snugged into our sleeping bags with a feeling of gratitude and the feeling of triumph was not missing when we saw that wind was powerless against the creation of our hands.

The longer we laid captive there inside, the more desperately we desired to go back again towards the light, towards the blinding sun that gave warmth and life….

And then we finally got out again from the darkness, we felt like the sky shone lighter and bluer than ever before, that the glacier glittered in sunlight in richer colours, and that Mt Flora’s ridged hillsides rose skywards more majestically than ever. We filled our lungs with the clean fresh air and a feeling of freedom brimmed our hearts amidst our captivity.

—

For pictures of the stone hut remains check out the Melting History blog.

Fredrik Bertilsson came to the Division of History of Technology, Science, and Environment in 2018. His main research focus is within the area of knowledge management and research policy.

Fredrik Bertilsson came to the Division of History of Technology, Science, and Environment in 2018. His main research focus is within the area of knowledge management and research policy.

This article contributes to the research on the expansion of the Swedish post-war road network by illuminating the role of tourism in addition to political and industrial agendas. Specifically, it examines the “conceptual construction” of the Blue Highway, which currently stretches from the Atlantic Coast of Norway, traverses through Sweden and Finland, and enters into Russia. The focus is on Swedish governmental reports and national press between the 1950s and the 1970s. The article identifies three overlapping meanings attached to the Blue Highway: a political agenda of improving the relationships between the Nordic countries, industrial interests, and tourism. Political ambitions of Nordic community building were clearly pronounced at the onset of the project. Industrial actors depended on the road for the building of power plants and dams. The road became gradually more connected with the view of tourism as the motor of regional development.

Full article: Politics, industry, and tourism: The conceptual construction of the blue highway

Fredrik Bertilsson

Många av samhällets grundläggande funktioner bygger på vägtransporter. Utbyggnaden av det svenska vägnätet under efterkrigstiden spelade stor roll för samhällets utveckling. Vägar är inte bara materiella konstruktioner. Meningsskapandet kring vägar pågår i förhållande till bredare sociala, ekonomiska, politiska och kulturella förändringsprocesser. I historien om det moderna vägnätets expansion under andra halvan av 1900-talet står ofta den tekniska expertisen eller betydelsen av personbilen i centrum. Turismens inflytande har väckt mindre intresse i den historiska forskningen. Blå vägen är ett exempel på hur politiska initiativ, den industriella utvecklingen och turistnäringen samverkade.

Blå vägen går nu från Mo i Rana vid den norska atlantkusten genom Västerbotten i Sverige, Österbotten i Finland och till Pudozj nära Petrozavodsk (Petroskoj) i Ryssland. Numer betraktas vägen vanligen som en turistväg men flera intressen låg bakom dess tillkomst. Initiativet till att bygga vad som senare blev Blå vägen togs på 1950-talet men det fanns färdvägar och marknadsplatser längs sträckan långt tidigare. Vägen mellan Umeå och Lycksele byggdes under första delen av 1800-talet. Blå vägen invigdes 1964 och blev i början av 1970-talet en europaväg. Namnet Blå vägen anspelar på att vägen går längs med Umeälven i Sverige men det lär i själva verket ha tillkommit efter att vägen markerats ut på en karta med en blåfärgad penna.

Blå vägen förankrades i ett politiskt arbete med att förbättra relationerna mellan Sverige och Norge efter andra världskriget. Det skapades en större rörelsefrihet mellan de nordiska länderna. Från 1952 kunde skandinaver resa utan pass mellan Sverige, Norge och Danmark. Passfriheten sträckte sig till Finland 1953 och Island 1955. Passkontrollen för samtliga resande flyttades till Nordens yttre gränser 1958. Det fanns under mitten av 1960-talet förhoppningar om att Blå vägen skulle dras ända in i dåvarande Sovjetunionen, vilket skulle bidra till att öppna upp de rigida gränserna mellan Öst och Väst under kalla kriget. Det dröjde till slutet av 1990-talet innan den vägsträckningen blev verklighet.

Den stora statliga planen för utbyggnaden av svenska vägnätet som presenterades i slutet av 1950-talet utgjorde en grundplåt för moderniseringen av de svenska vägarna. Bättre vägar skulle lösa dels ett kapacitetsproblem som skulle uppstå när fler fordon måste trängas på vägarna, dels ett säkerhetsproblem: trafikolyckorna befarades öka om vägarna inte förbättrades. Blå vägen inrymdes inte i den ambitiösa vägplanen. Vägen finansierades istället av Vattenfall och genom kommunala insatser.

Industriella aktörer hade tydliga intressen i en ny väg. En väg till en isfri norsk hamn skulle gynna den omfattande transporten och exporten av trä och virke. Viktiga delar av den väg som fanns var stängd vintertid. Skogsindustrins intresse i en moderniserad väg förstärktes av att flottningen alltmer ersattes av lastbilstransporter. Det fanns också ett tydligt intresse av att rusta upp den befintliga vägen för att klara av den trafik som uppstod i samband med att vattenkraftverken i Umeälven byggdes.

Fler intressenter involverades successivt. Den så kallade Blå Vägen-föreningen bildades i början av 1960-talet för att påskynda vägbygget. Föreningen bestod av representanter från politiken, näringslivet och turistnäringen. Det fanns representanter även från Norge och Finland. Kommersiella intressen stod ofta i fokus. Blå vägen-föreningen fick draghjälp av den svenska pressen där den kunde föra ut sitt budskap och stärka intresset för vägen både lokalt, regionalt och nationellt. Det gjordes även program i radio.

Blå vägen betraktades som en lösning på flera stora problem som Västerbottens inland ansågs stå inför, inte minst vad gällde avfolkning och arbetslöshet. Byggandet av vägar hade varit ett sätt att skapa arbetstillfällen under lågkonjunkturerna under 1920- och 1930 talen. Vägarbetet var ett säsongsbetonat komplement till övriga inkomster men det genomfördes vanligen under svåra omständigheter och ersättningen var ofta låg. Från ett längre perspektiv var det ett led i en omställning från ett jordbruksbaserat samhälle till ett där industrier och servicenäringar har större betydelse.

Vägens betydelse för turistnäringen betonades allt tydligare. Västerbotten låg länge efter andra områden vad gällde turismen. Redan i slutet av 1800-talet fanns turistförbindelser till fjällvärlden i Abisko. Turistnäringen i Jämtland var också utvecklad. När Västerbottens turism drog igång på allvar var det inte längre aktuellt att satsa på järnvägar. Bilen betraktades dessutom som ”folkligare” än järnvägen.

Blå vägen laddades med stora förväntningar. I riksmedia målades en bild upp av en omfattande turisttrafik. Enligt en uppskattning i Expressen (26/7 1963) skulle hundratusentals turister åka längs Blå vägen under det första året och sedan väntades trafiken öka. Dagens Nyheter (7/12 1963) påpekade att Hemavans fjällhotell kunde byggas ut i samband med Blå vägens expansion. Turismen till skidanläggningarna i Västerbottensfjällen är en viktig inkomstkälla. Det går att spekulera i vilken betydelse turistekonomin fått för utvecklingen av skidnäringen i stort. Från Tärna kommer flera av Sveriges mest kända skidåkare, bland andra Anja Pärsson, Ingmar Stenmark och Stig Strand.

Marknadsföringen av Blå vägen spelade på stereotyper eller fantasier om norra Sverige. Det talades om en omvandling av landskapet, ett slags återanvändning av det gamla jordbrukssamhället som skulle bli till pittoreska vyer för moderna turister. Enligt Göteborgs-Tidningen (21/6 1964) gav en resa längs Blå vägen ”hela skalan av det svenska landskapets olika nyanser”, dvs. en modern universitetsstad i Umeå, bördig jordbruksbygd i kustlandet, gles bebyggelse i inlandet, ”milsvida skogar” och en ”fascinerande fjällvärld där snön ligger kvar året runt”. Samtidigt skulle turisterna få ta del av det moderna samhällets alla bekvämligheter.

I många nutida sammanhang beskrivs Blå vägen främst som en turistväg utan att kopplingarna görs till det industriella arvet. De politiska betydelser som satte igång vägbygget träder också i bakgrunden. Den berättelsen ska ses i ljuset av de historiska narrativ som nu etableras om norra Sverige där turismen snarare än den industriella produktionen och utvinningen samt förädlingen av råvaror står i fokus. Blå vägens historia ger en inblick i hur politiska ambitioner, den industriella utvecklingen och efterkrigstidens turistnäring hängde ihop. Det skapades nya former av samverkan men det fanns också slitningar mellan olika intressen.

*

Texten bygger på en artikel som publicerats i Journal of Transport History, ”Politics, Industry and Tourism: The Conceptual Construction of the Blue Highway” (https://doi.org/10.1177/0022526620979506). Forskningen har finansierats av Brandförsäkringsverkets stiftelse för bebyggelsehistorisk forskning.

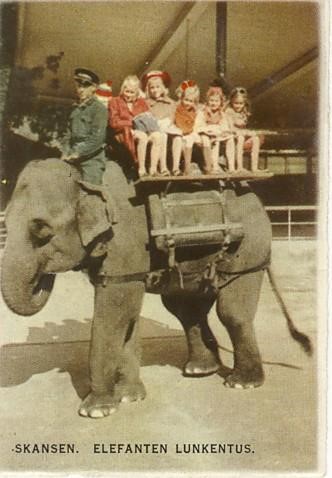

The Division’s kickoff at Skansen this year gave opportunities to reflect on the institutional combination of open-air museum and zoological park that this location embodies. The keeping of Nordic animals can be understood historically as part of the same identity-building project as Skansen as a whole, representing Swedish nature similar to how the collected buildings represent Swedish culture. However, other animals are there too, and have been almost since Skansen opened. From monkeys to turtles, penguins, and walruses, exotic animals have always been big attractions, important to the economy and strategy of the park. The presence of a range of animals in the center of the capital also means that Skansen has long been a site for the creation and mediation of animal-related knowledge. Only a few days after the kickoff, I stumbled on a curious account in the archives that highlight both these aspects of Skansen’s history. We might call it “The Illness and Death of Lunkentuss the Elephant.”

Lunkentuss (née Rani) was an Indian female elephant born in the 1920s and bought by Skansen in 1931. She was the first elephant Skansen owned—following a highly successful experiment with a borrowed one—and became a very popular exhibit. She drew large crowds, particularly in the warm season when children were able to ride the compliant and docile animal around the grounds. But already in 1938, when still very young by elephant standards, Lunkentuss began to show slightly impaired movement in her right hind leg. Fearing for the future of its crowd-pleaser, Skansen brought in its consulting veterinarian Vilhelm Sahlstedt, professor of chemistry and physiology at the Royal Veterinary College.

Confronted with Lunkentuss, Sahlstedt faced several problems that required the adaptation of established practices and the development of new knowledge. He initially knew little of elephants from a clinical perspective. The detailed leg examination that would be carried out on horses with similar symptoms could not be performed on Lunkentuss, as her leg was too big. Resorting to observation and extending what he knew of the movement of horses and other big mammals, Sahlstedt nevertheless was able to conclude that she was suffering from an inflammation of her knee joint and proceeded to treat her accordingly, with local and internal application of salicylates. At first Lunkentuss refused the medication, but Sahlstedt found that by placing it in a “piece of bread or some suitable root vegetable” she would eat it. The therapy took effect; Lunkentuss could once again carry children around. The leg problems periodically reoccurred, but repeated treatments ensured that she continued to serve as a central attraction at Skansen.

In the fall of 1939, Lunkentuss’ general condition worsened. She would eat less, now showed symptoms of pain in both hind legs, and resisted her normal exercise. Sahlstedt was recalled but again the body of the elephant resisted the application of normal clinical techniques. Auscultation was possible, but revealed nothing remarkable; palpation was not—the skin was too thick and the animal simply too voluminous. Though at a loss for a diagnosis, Sahlstedt tested a pharmaceutical treatment based on small doses of arsenic. This stimulated Lunkentuss’ appetite, but her condition did not improve and she grew increasingly thinner. She continued to draw crowds, but after the spring of 1940 could no longer be used for rides. In early 1941, conceding that she was unlikely to improve and with the state of her legs deteriorated to the point that it was impossible to exhibit Lunkentuss outside of her stables, Sahlstedt finally proposed to put the animal down.

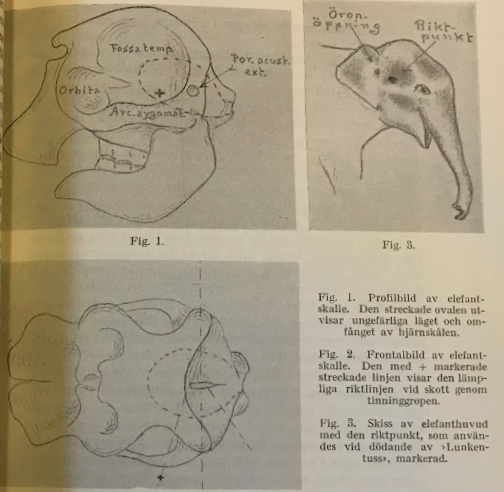

With that, however, another significant problem arose. No one knew how to best dispatch an elephant. It seemed clear that a rifle had to be used, but since elephants have very large skulls but not very large brains, it was difficult to determine where to place the shot. The veterinary literature Sahlstedt consulted provided only vague hints, and a search for big-game hunters (who were presumably knowledgeable in such matters) failed to locate one in Stockholm. Rash experiments were out of the question, not only for humanitarian reasons but also because Lunkentuss was a well-known and charismatic animal that many people had a relation to. A botched killing might thus end up in the press, which would be a public relations nightmare. Eventually, however, Sahlstedt came up with an innovative approach: he approached the Museum of Natural History and, together with one of its curators, made measurements on elephant skulls from the museum collections. From these, Sahlstedt concluded that the killing shot should be placed in the fossa temporalis at the side of the skull from a certain distance and angle. A special hunting rifle was then acquired from the Huskvarna works and its penetrative power with different kinds of ammunition was tested by firing on sets of pinewood planks. When sufficiently satisfied both with his anatomical investigations and with the weapon, Sahlstedt had Lunkentuss immobilized and marked the aimpoint with paint on her head. Chief Animal Handler Johansson, known to be a good shot, was tasked with carrying out the killing. On February 17, 1941, he proved Sahlstedt’s calculations correct. Squarely hitting the intended point, Lunkentuss died instantaneously.

The story of Lunkentuss points to a history of Skansen in which exotic animals were important actors playing active parts in making the park what it was, even as the park made them what they were. While healthy, Lunkentuss generated much publicity and revenue. She became something of a symbol of the park, who, as she trudged around the pathways with kids on her back, acted out a defining experience of a Skansen visit. As a sick animal, her victimization and commodification becomes clearer, in a way that highlights how the story is also of the construction and nature of veterinary expertise.

Because Sahlstedt had little theoretical or practical experience of elephants, his encounter with Lunkentuss triggered experimental and investigative work that created new knowledge of their lives and deaths. He learned how to treat their knee joints, how to feed them medicine, how they could and could not be examined clinically, and ultimately also—by enrolling the Museum of Natural History and its collection of already-dead elephants—how to kill them. He published an account of these findings in a veterinary journal, arguing that they might be useful for his colleagues if, for example, they were consulted by elephant-keeping circuses. Part of the motivation was perhaps also pride in his innovative application of anatomical expertise to the skulls from the Museum of Natural History, generating new knowledge of clear practical value.

But Sahlstedt’s expertise only took him so far. The final nature of Lunkentuss’ illness eluded him. He was then faced with a tension central to all veterinary practice, emerging from the fact that patients and clients are not only distinct, but the former are also the property of the latter and their interests need not overlap. In the case of Lunkentuss, Skansen’s interest in keeping a key attraction alive had to be balanced against the fact that Lunkentuss was in pain but could not be diagnosed nor efficiently treated. Sahlstedt’s own account of the affair—which is also the basis of my narrative—can in part be read as a defense of his management of this tension, particularly his decision to wait a rather long time before finally having the animal put down. Though Lunkentuss was not healthy, he argued that she still retained some appetite and seemed “lively and interested in her surroundings,” a behavior that did not suggest great suffering. Balancing her value for Skansen against the perhaps only light pain she was experiencing, Sahlstedt thought his wait-and-see approach justified until there really was no more hope for improvement. This medical judgement was to Skansen’s advantage. It did not make Lunkentuss’ condition public and the ailing elephant continued to be used for publicity and in advertisements through 1940. When announcing her death, Skansen suggested that she had acutely taken ill, a claim that was reproduced by the press and has also shaped later accounts of Lunkentuss’ life (these sometimes include the claim that the cause of her illness was the accidental ingestion of broken glass, a theory not mentioned by Sahlstedt nor, apparently, supported by the autopsy performed at the Veterinary College). This obscured and obscures the fact that the animal was in fact chronically ill and under veterinary care for three years before she was killed.

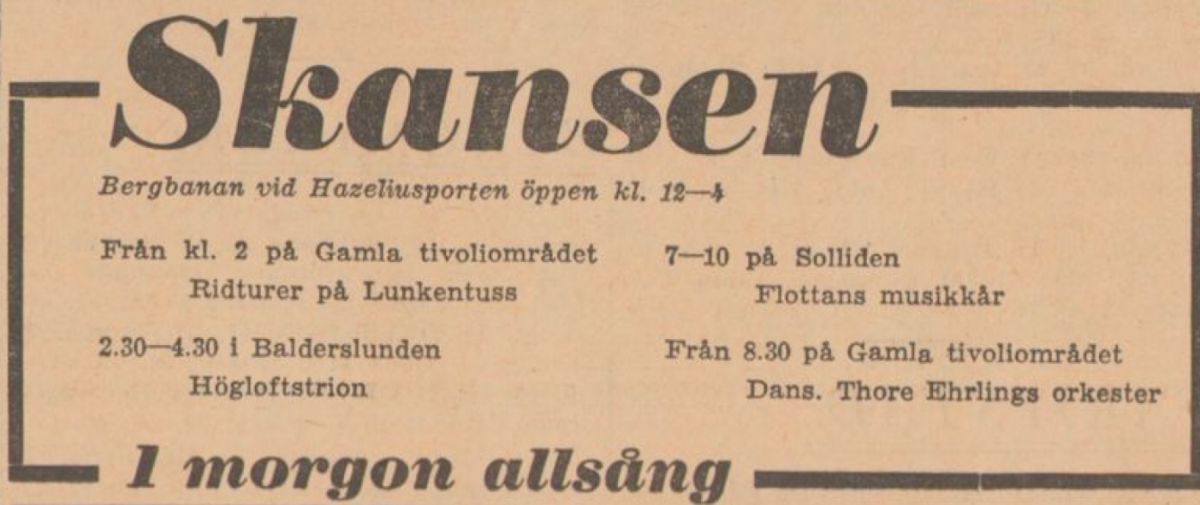

Advertisement for Skansen printed in Svenska dagbladet, May 27, 1940, offering rides on Lunkentuss. She was already unwell by then and lost the ability to perform this task soon after.

It is understandable that Skansen preferred to keep quiet about Lunkentuss’ long illness, since being a very public animal, the way she was treated had the potential to impact strongly on the public appreciation of the park. The veterinary expertise involved was likewise at risk of public scrutiny. Sahlstedt, who had been the vice-chancellor of the Veterinary College and was in some respects a professional leader, was not insensitive to this. In his account, he reflected that fair or not, a veterinarian had “to be prepared to be asked almost anything that has to do with animals,” no matter the particular animal’s prevalence in Swedish veterinary practice. This goes some way to explain the care he took in giving Lunkentuss a painless death: Sahlstedt noted twice in his account that it was instantaneous, a wording that also recurs in the press coverage (presumably reflecting a Skansen statement). It suggests something of how the fate of Lunkentuss was not only closely bound up with the construction and nature of veterinary expertise, but also with its mediation and how it self-consciously dealt with an unusually public patient.

Finally, Lunkentuss also highlights the importance of historical attention to the agency of animals and to human–animal interactions. Lunkentuss’ own behavior and actions were constitutive of the role she came to play at Skansen, as well as of the development of veterinary knowledge of and around her. It was her compliance with her handlers’ instructions and her docile nature when interacting with visiting children that created the position she acquired in the zoo and thus also many people’s image of Skansen. When she began resisting certain interactions (feeding, exercise), veterinary expertise was brought in, creating new forms of interaction that enabled new knowledge development. This is not to say that there was symmetry of power: Lunkentuss was subject to human action over which she had limited control. But she retained her ability to express experiences and act in a range of ways that all influenced the dynamics of interaction between herself, her handlers, riding children, and the veterinarian—and by extension she thus also shaped the interaction between Sahlstedt, Skansen, and the general public. In this respect, Lunkentuss illustrates the importance of exploring the past lives of animals, as we might find that the way in which these lives were lived impacted on a wide range of developments otherwise thought of as human-driven.

Even Lunkentuss’ final interaction with Chief Animal Handler Johansson is of historical significance. The immobilized and marked elephant had little influence left by then—but the successful killing validated the expertise that had been created around Lunkentuss’ illness and death. Unlike a botched attempt, Sahlstedt’s aimpoint and Johansson’s shot served to confirm that Skansen could take responsibility for elephants in life and in death. Consequently, another young elephant, Bambina, could simply take Lunkentuss’ place, and elephants would continue to draw crowds to the park until 1992.

The account is primarily based on, and all quotes (translations by me) are from, A. V. Sahlstedt, “Från Skansens zoologiska trädgård: En elefants sjukdom och död,” Svensk veterinärtidskrift 46, no. 4 (1941). I have also reviewed press material from 1939, 1940, and 1941 in the Royal Library.

This blog post hints at perspectives and approaches I will work with—albeit in an agricultural rather than an exhibition context—in my new project at the division. Entitled “Clinical Breeding: Cattle Reproduction and Veterinary Expertise in Sweden, 1922–1975,” the project will examine the co-production of human–animal relations, veterinary expertise, and reproductive technologies in the context of mid-twentieth century Swedish dairy farming. I will spend two years of the project as a visiting researcher at the Centre for the History of Science, Technology & Medicine, King’s College London.

Further reading:

An excellent book on elephants as actors in the context of American circus is Susan Nance, Entertaining Elephants: Animal Agency and the Business of the American Circus (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013)

The longer history of Skansen’s elephants is detailed in Ingvar Svanberg, “Indian Elephants at Skansen Zoo,” The Bartlett Society Journal 21 (2010).

For a brief overview of the “animal turn” in history (including a short bibliography), see Dan Vandersommers, “The ‘Animal Turn’ in History,” https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/november-2016/the-animal-turn-in-history