Authors: Alejandra Mancilla, professor in Philosopy, UiO & Peder Roberts, associate professor in Modern history, UiS & researcher, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment, KTH

Norway is one of the 29 consultative parties to the Antarctic Treaty, which marks its 60th anniversary in 2021. Many celebrate that the treaty has achieved peace and scientific cooperation. Additionally, it is 30 years since the Protocol on Environmental Protection (widely known as the Madrid Protocol) was agreed. Since then no further legal instruments have been developed to deal with new challenges – above all, the climate crisis. We argue that the Antarctic Treaty does not lack the necessary tools to address this challenge, and that instead it is a matter of more ambitiously interpreting the texts that already exist, and the responsibilities of the individual countries involved.

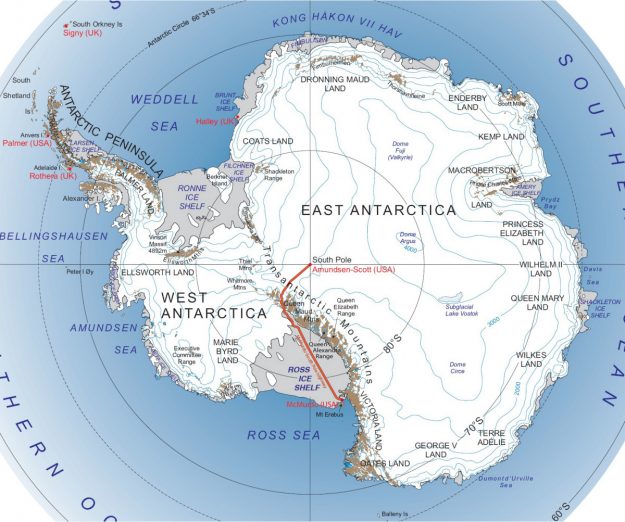

The Madrid Protocol states that the parties commit to protecting “the Antarctic environment and dependent and associated ecosystems.” This phrase (which occurs nineteen times in the text) leads to the question: what does it mean to protect ecosystems that are dependent and/or associated with Antarctica? The Protocol, like the Treaty itself, covers the area from the South Pole to latitude 60 degrees south, but to attain that goal it is necessary to act further north. Actions outside the geographic boundaries of the Antarctic Treaty should therefore be taken into account when evaluating the extent to which a state fulfills its commitments to protect Antarctica.

The Protocol also asserts that Antarctica has “intrinsic value”. Intrinsic value stands in contrast to instrumental value. Using Antarctica as a laboratory is an example of the latter, where Antarctica functions as a means to achieve the end of increasing scientific knowledge. Intrinsic value, on the other hand, demands that we treat Antarctica as an end in itself. What exactly that means is a discussion that the Antarctic Treaty parties are yet to have, but which could lead to a more ambitious interpretation of the Protocol’s mandate.

The processes that drive climate change and loss of biodiversity do not follow political geographical boundaries. For Antarctica, it is not enough to regulate activities within the Treaty area itself: activities beyond must also be considered. The states that signed the Madrid Protocol committed themselves, in a way, to protect the whole world. It is high time that citizens of the signatory states voiced that demand, particularly in the context of elections. Committing to meet or exceed the targets set in the Paris Agreement would be a good start.

As a founding member of the Antarctic Treaty that continues to be active in the continent, Norway should take the lead in this process. The country has a self-image as an enthusiastic advocate of human rights and environmental causes at the global level. If it wishes to live up to its reputation, Norway ought to begin by stopping issuing new permits for oil exploration and taking concrete steps toward reducing fossil fuel production. Thus can Norway truly make a contribution to protecting Antarctica.